The residents of Whitehorn in Northern California are battling climate change to save the Mattole River watershed and its delicate habitat.

April 27, 2013

For the residents of Whitethorn, a California community nestled among the coastal redwoods 200 miles north of San Francisco, the impacts of climate change have been a reality for over a decade.

The only source of water for this small secluded town near the Lost Coast is the 62-mile Mattole River. In the summer of 2002, the river with its grasslands, ancient trees, endangered native-salmon, tailed frogs, spotted owls and bald eagles, stopped flowing and its tributaries dried up.

Locals looked on in horror as hundreds of juvenile salmon withered away and dried leaves crunched underfoot in the streambeds.

“The water was gone” said Marisa Formosa, a 26-year-old, eighth generation local, who remembers the disaster vividly. “Some people tried to put the fish in buckets and relocate them, but there wasn’t anywhere to go,” added Formosa, whose grandmother was a character in Jack Kerouac’s novel, “On the Road.”

More than a decade ago, when gasoline was only $1.46 a gallon, and Hummers were popular, then-Governor Gray Davis and his experts were just beginning to consider the possible ill-effects of climate change.

Today, 11-years after Whitethorn got its first hit of climate change fall out, Governor Jerry Brown and his experts have declared war against the perilous threat under the Climate Action Initiative.

According to California’s official website, climate change is expected to have significant and widespread impacts on the state’s economy and environment, affecting water supply, the coastline, forests, agriculture, and all of the natural wonders – including old-growth forest stands and ancient rivers like those near Whitethorn.

Government agencies, including the Bureau of Land Management and the Department of Fish and Game, are closely monitoring bold strategies being used in Whitethorn to battle the effects of climate change.

After most of Whitethorn’s water evaporated in 2002, the resilient community banded together to fight climate change.

The residents of Whitethorn are familiar with overcoming adversity.

In 1987, the community joined forces and formed a nonprofit called Sanctuary Forest Inc. (SFI), which saved over 10,000 acres of old-growth forest from logging.

SFI Executive Director Tasha McKee and Sanctuary Forestors including Marisa Formosa and Campbell Thompson began compiling stream-flow data and investigating the causes of the low water flow problem that appeared in 2002.

“Tasha really led the way,” Thompson said.

After years of study, McKee confirmed that climate change including higher temperatures, less precipitation and longer dry seasons, were the primary contributing factors to low water flow levels, exacerbated by poor land-use practices.

The detailed study supported the general consensus around Whitethorn that the ever-changing drier climate was to blame.

Formosa said the winter snow-falls which used to dust the forest – sometimes as deep as six-inches – disappeared and that the summer dry seasons are longer and hotter than ever before.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) the Whitethorn region only received 14.72 inches of rain between March and November of 2002, compared to a normal average of 34.76 inches in the same time period.

With less rainfall the community could not afford to use stream water in the summer. McKee realized that the numerous streams within the community were also choked with hard-packed soil that caused the rainfall to roll away like water on glass instead of saturating into the ground.

Not only was precious water washing away, but the shallow, hard streams were less than optimal for the native-salmon and the surrounding forests whose roots depended on the ground water.

So Mckee developed two strategies to save the community’s water resources while helping to sustain the local wildlife habitat.

The first was the grant-funded Sanctuary Forest Water Storage and Forbearance program. SFI installed thousands of gallons of water storage tanks that accumulate rainfall during the wet season, which residents now use instead of pumping from the river and streams during the critically dry summers.

Formosa said the water storage program is so successful that even the more private residents who shy away from outside interaction, have bought their own tanks and participate unofficially.

Driving through the landscape of Whitethorn and the surrounding valley, green and brown rainwater tanks dot the landscape and color the yards of homesteads.

Pumps for the tanks come equipped with intake fish screens to prevent damage to small fish.

The second strategy is the Groundwater Recharge and Habitat Enhancement Program.

The strategy is based on natural functions once provided by abundant wood in the streams and utilizes channel-spanning log structures to create pool habitats for fish, recover groundwater storage, increase summer stream flows, and restore floodplain connectivity.

The pilot program recently launched at Baker Creek, one of many tributary streams that flow from the Mattole River into the forests.

The restored Baker Creek can now hold more rainwater and is absorbed into the ground more efficiently.

SFI hatched the plan in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management who funded the project, and other nonprofit partners including the Mattole Salmon Group and the Mattole Restoration Council.

SFI excavated the barren, hard-packed Baker Creek and rebuilt it to restore groundwater, stream flow, and resilience to climate change through recovery of natural processes.

The newly restored Baker Creek looks like a model of the perfect stream with immaculately placed rocks and logs – resembling a Japanese water garden flowing through the forest.

One can see the water accumulate far from the creek toward the forest line, and groundwater measuring devices rise from the forest floor so that scientists can track the progress.

McKee said that even before the rains, pools begin to form upstream of the logs and the groundwater began to rise.

Recent storms have swelled the stream.

Not only does the restored stream hold water in the ground water table more efficiently, charging the earth’s water storage, but the stream runs deeper and slower, providing the ideal habitat for endangered native-salmon.

SFI monitors Baker Creek closely along with government agencies to watch for any unforeseen side-effects that could harm the fragile ecosystem.

If the ambitious pilot program is deemed successful by the government, then SFI could gain approval to restore every stream in the valley, further protecting the environment from climate change while creating a new habitat for endangered native-salmon.

“Sanctuary Forest is very excited to share the beginnings of our first project at Baker Creek,” Mckee said.

SFI Vice President Eric Shafer, who knows the surrounding forests better than most, said that he is very confident in the project.

But, if the climate changes too much, and the delicate fog which the old-growth coastal redwoods depend upon for survival, disappears, then even the new and improved streams and the rain tanks might not help to save the coastal redwoods that SFI has fought to protect – or the endangered animals that depend on the groves of virgin old-growth trees to survive.

Renowned physicist and cosmologist Stephan Hawking warned that climate change is one of the greatest threats posed to the future of human-kind and the world.

Unless the government and Californians succeed in significantly reducing carbon emissions under Brown’s determined Climate Action Initiatives – setting an example for the world to follow – the natural treasures of this generation may disappear.

And, if human-kind continues to discharge massive amounts of carbon and other poisons into the environment unabated – human-kind too could also disappear.

Just like the juvenile salmon did when Baker Creek dried up.

- Baker Creek before restoration. Photo via Sanctuary Forest.

- Baker Creek after restoration. Photo by Sabrina Wong.

- Baker Creek channel spanning log structure after restoration. Photo by Sabrina Wong.

- Sanctuary Forest Executive Director Tasha McKee measures water flow levels. Photo via Sanctuary Forest.

- Water level measuring device. Photo by Sabrina Wong.

- Marisa Formosa at Baker Creek. Photo by Sabrina Wong.

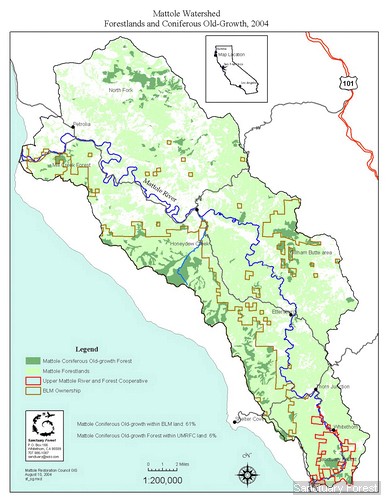

- Map of the Mattole River watershed.

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

June 3, 2013 at 10:53 am

Update on this story: “Build it and they will come.” Not long after the last of the winter rains fell, a new school of rare, juvenile, native coho salmon were spotted in the newly rebuilt Baker Creek. A true miracle!