By Oliver Luby, first published in the San Francisco Chronicle

November 4, 2008

If there is a gold standard for watchdogs of political campaigns, that gold standard is to follow the gold. Ever since the Watergate era, the public has insisted on disclosure of political money – who gives it, who gets it, how it is spent – and the public has insisted on some safeguards against practices like money laundering that hide the true source of campaign money.

So it is more than alarming that San Francisco’s Ethics Commission, which is funded with more than $2 million in taxpayer money, has decided it will ask no questions of major donors – those who contribute $10,000 or more to political campaigns.

The Ethics Commission refused to ask questions when there were clear signals of illegal campaign activity in the 2005 Community College bond campaign; instead it acquiesced to the demands of campaign attorneys that following the money of major donors is a low priority. It still refuses to follow up on major donors. Last year, The Chronicle broke the story on how money owed to City College of San Francisco was instead laundered into a community college political campaign. A subsequent internal investigation by the college trustees confirmed the transfer. Tens of thousands of dollars were “contributed” after college officials told contractors to divert the money they owed City College into a political fund.

Eighteen months earlier, the Ethics Commission was warned that money laundering might have taken place.

I know, because my job then and now is to be an Ethics Commission officer charged with following the money. I noticed that the political campaign reported contributions from donors who never filed or partially filed. When I called to tell one of them that he was required to report contributions of $10,000 or more, the contractor told me he never intended to make a political contribution. He only wrote the check that way at the request of the community college.

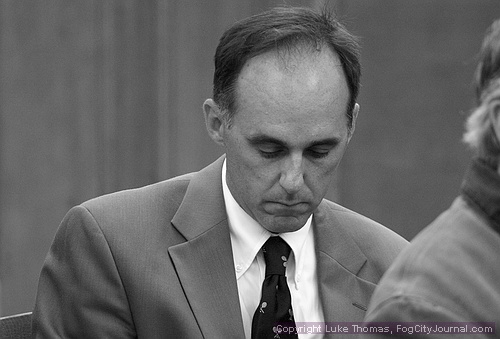

I wrote a memo in November 2005 to Ethics Commission Executive Director John St. Croix telling him “there may be serious impropriety present in this case necessitating an investigation as well as perhaps even a referral to the District Attorney’s office due to the possibility of criminal conduct.”

He instructed me not to speak about my report. The episode stayed hidden until The Chronicle broke the story more than a year later.

Ethics Commission Executive Director John St. Croix.

I identified delinquent major donors who failed to report for elections from 2000 to 2004. My work resulted in scores of disclosures, $200,000 in penalties, and the discovery of significant discrepancies between what campaigns reported and what their major donors reported. The result: a backlash against investigating major donor contributions.

At a 2005 Ethics Commission meeting, attorney and campaign adviser Jim Sutton lobbied that “it was not appropriate for the Commission to make the non-filing of major donor reports such a high priority,” according to the minutes. Sutton’s firm also served as the paid consultant to the community college in the bond campaign.

Attorney Jim Sutton

When the media asked St. Croix why the community college money laundering hadn’t been uncovered years earlier, he said, “I don’t know who dropped the ball. But at the time, we had less staff and there were a lot of things we were supposed to do and we weren’t doing.”

Today, it remains the commission’s policy not to follow up on major donor contributions. My memo identifying 2005-2006 delinquent major donors received no response at all. In mid-2007, I requested authorization to contact the delinquent donors. The executive director informed me that major donors were not a priority because reporting was of minimal value – an eerie echo of the political consultants who rely on major donors to pay the bills.

I later wrote a third memo, this time to the commissioners, including the decision to end enforcement of major donor delinquencies and how such a delinquency had played the critical role in uncovering the community college money laundering. Subsequently, the Sutton firm again testified to the Ethics Commission that donor enforcement was “awful.”

This year, I submitted a fourth memo, this time identifying the 2007 delinquent major donors. It also was ignored. Required disclosure regarding a half-million dollars or more has still not being filed. The policy remains: “Don’t tell, don’t ask” – just as political campaigns would like it.

What I wrote in 2005 would have remained locked away from public view except that I requested a copy of my own memo under San Francisco’s Sunshine Ordinance. Once it was released to me, it became a public document.

In making this public now, I rely on whistle-blower protection and another well-proven adage: The public has a right to know.

Oliver Luby is the fines collection officer for the San Francisco Ethics Commission. He submitted this commentary as a private citizen.

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

No Comments

Comments for Ethics Whistleblower Exposes Money Laundering Cover Up are now closed.