By Terry Canaan

November 26, 2008

The presidential pardon has been a controversial matter since day one. Virginian George Mason would’ve been one of the signatories to the new constitution of the United States of America, but disagreed with basic ideas in the document — including the pardon — and refused to sign. On the power of the pardon, Mason worried that a president who had “secretly instigated to commit crimes” with others might use it to prevent “a discovery of his own guilt.”

But it was Alexander Hamilton who prevailed in that debate. “The principal argument for reposing the power of pardoning in the chief magistrate is this: In seasons of insurrection or rebellion, there are often critical moments when a well-timed offer of pardon to the insurgents or rebels may restore the tranquility of the commonwealth,” he wrote in the Federalist Papers. Unfortunately, Hamilton only foresaw the presidency as a position held by “a single man of prudence and good sense.”

Which recent resident of the White House doesn’t that sound like to you? Mason’s argument is starting to look better.

Still, Hamilton’s argument also makes sense. The idea is that executive clemency could be used quickly to avoid a national emergency. Washington used it to end the Whiskey Rebellion, an uprising of Pennsylvanians who refused to pay taxes on booze. Andrew Johnson granted clemency to the entire confederate army — a pretty common sense move that still wasn’t without controversy. His opponents accused him of restoring the right to vote to most of the south for political gain.

But it pays to remember that, as historically significant as the Federalist Papers are, they aren’t law. Hamilton’s opinion of the pardon has no more legal basis than his confidence that there’d never be a President Numbskull. The law is in the Constitution and that reads, “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices, and he shall have Power to Grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.”

There you go then, that’s the law. As you can see, it’s not extremely limited. The Justice Department’s Office of the Pardon Attorney (that’s right, there’s an office on the Attorney General devoted solely to pardons) tells us, “The President cannot commute a sentence for a state criminal offense. Accordingly, if you are seeking clemency for a state criminal conviction, you should not complete and submit [a] petition.” This is because the Constitution limits them to “Offences against the United States.” The only other limitation is impeachment.

Still, you can see how it could be used justly without limiting yourself to Hamilton’s rationale. The pardon has been used put aside disproportionate sentences. The idea of being “tough on crime” is nothing new and it’s had people imprisoned for incredibly stupid things.

But the pardon is best remembered as being used in a way that George Mason worried about. Gerald Ford pardoning Nixon “for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed or taken part in…” Good news for Nixon, bad news for Ford. It probably cost him his the election (you can’t really say “reelection” in this case) in 1976. Many wondered if Ford had “bought” Nixon’s resignation with the promise of presidential mercy.

Later pardons were controversial as well. Bill Clinton’s pardons of business partner Marc Rich and half-brother Roger Clinton were widely considered abusive, but completely legal. George W. Bush’s commutation of Scooter Libby was also met with outrage. But it was just as legal as Rich’s and Clinton’s. In fact, Libby’s pardon was pretty much exactly what Mason had in mind when he warned of an executive using the power of the pardon to cover-up his own guilt.

Bush didn’t grant a full pardon for Libby, but reduced the jail time from 30 months to none, saying the jail time was excessive. Libby still had the conviction and a quarter-million dollar fine, but he was walking around a free man, where he wouldn’t have been otherwise. But there were other benefits — at least, for Bush.

“In part, Bush may have stopped short of a full pardon precisely to keep Libby and other White House aides away from Democrats on Capitol Hill. Investigators in Congress are eager to call Libby to testify about the Plame case and prewar Iraq intel — an invitation Libby can continue to resist by claiming he can’t talk as long as his appeal remains alive in the courts,” Michael Isakoff wrote at the time. Bush managed to keep Libby out of jail but in the legal system.

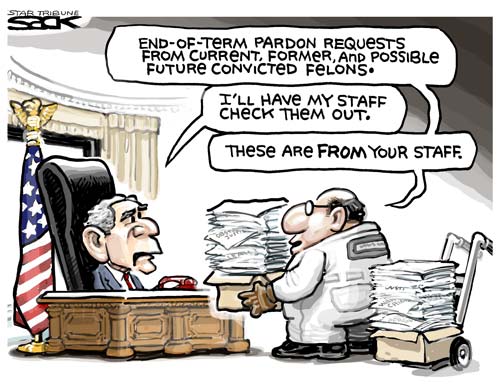

Not surprisingly, Bush is now being hit with a string of requests for pardons:

Among those seeking presidential action are former junk-bond salesman Michael Milken, who hired former solicitor general Theodore B. Olson, one of the nation’s most prominent GOP lawyers, to plead his case for a pardon on 1980s-era securities fraud charges. Two politicians convicted of public corruption, former congressman Randy “Duke” Cunningham (R-Calif.) and four-term Louisiana governor Edwin W. Edwards (D), are asking Bush to shorten their prison terms.

It remains to be seen how Bush will respond to these requests as his term ends. The president has used his broad pardon powers rarely during seven years in office, granting 157 pardons out of 2,064 petitions, and only six of 7,707 requests for commutations, according to an analysis by former Justice Department lawyer Margaret C. Love.

But the biggest possible pardon is the one that has lefties sweating — can Bush pardon himself? The answer is less than satisfying. No one knows.

Stephen M. Brown, Alternet:

According to attorneys whom I asked, there is no definitive legal answer. There is no case law on the subject and not even much legal analysis of the possibility. All there seems to be are three law review articles that analyze the self-pardon power with arguments for and against its legality. (I am convinced by the arguments against its legality, but given the present Supreme Court, who knows?).

Bush has had no trouble testing the limits of the law before. But it may be that the political question may be more important than the legal one. If Bush pardons himself, everyone will safely assume that he’s committed crimes. It’s extremely unlikely that Bush could commit any consequential crime alone, which means conspiracy. Where there’s a conspiracy, there are conspirators. Bush has spent the past eight years peppering Washington with loyalists, in order to extend his influence beyond his term. Bush can’t issue a blanket pardon — he has to name a specific individual or group of individuals — and, if this hypothetical conspiracy is broad enough, he couldn’t possibly find everyone who needs to be pardoned without a full-scale investigation of his own. I doubt there’s time left for that. The best Bush can probably do is just pretend nothing’s wrong and hope for the best — maybe leave the country, just to be safe.

In the end, I think it’s probably a lead pipe cinch that Bush is going to issue some sort of controversial pardon before he’s out. Probably not for Libby, but maybe for Cheney, Gonzales, or other suspected war criminals or possible corrupt cronies.

That’s not the bad news. The bad news is that there probably won’t be anything we can do about it.

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

November 26, 2008 at 12:41 pm

AND NOW FOR THE REALLY BIG PARDON

http://pacificgatepost.blogspot.com/2008/11/trigger-for-cheney-presidential-pardon.html

Stories just don’t get much better than this, but the Presidential pardon has to be abolished.