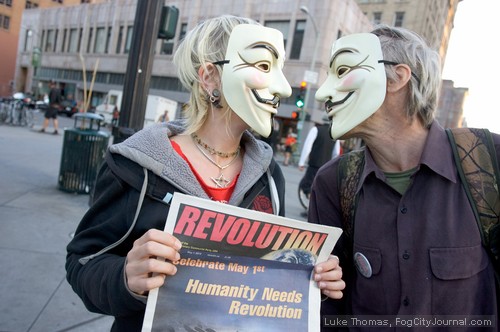

In the grand scheme of things, the fledgling Occupy movement has only just begun and is not going away anytime soon. File photo by Luke Thomas.

By Ben Vitelli, via Occupy Baton Rouge

June 12, 2012

People can’t seem to stop eulogizing the Occupy Movement.

Since the eviction of the protestors at Freedom Plaza last November, it’s become a media cliché to report on the “Death of Occupy.” Articles pop up all over the web, blithely reporting on the failed second wind of Occupy, this lackluster “American Spring,” and the May Day general strike that didn’t quite shut the system down.

It should be no surprise that the mainstream media is eager to report on Occupy’s supposed demise. Even ignoring the fact that the corporate-owned media has a strong desire to never see social movements such as Occupy succeed, the media, as a rule, generally needs to put a dramatic narrative to everything it reports. To them, every story ought to have a captivating story arch with a beginning, middle, and an end.

In the media’s eyes, the story that was Occupy began when the magazine Adbusters put out a call to Occupy Wall Street on September 17. Many people heeded the call, yet, according to the media’s story, the movement only received its dramatic momentum when cops were photographed attacking and pepper-spraying the nonviolent protestors. It reached its early demise when the police violently cleared out the various encampments. Now, except for a few curmudgeons who can’t seem to understand that Occupy is over, all that remains of Occupy is its populist rhetoric of the 99%—which has been dutifully hawked up by Democratic front-groups such as MoveOn.org to help refuel the Obama election machine.

This popular narrative of Occupy, with its clear-cut beginning, middle, and end, has been so successful that even those who are still active within the Occupy movement can’t help but absorb parts of it. Lately, many General Assemblies sometimes border on something closely resembling a public support group. On the internet, vaguely self-congratulatory Paul Krugman-y articles, applauding Occupy for “at least shifting the public dialogue,” are posted and reposted to different Occupy-related Facebook groups to remind each other that Occupy at least had a little bit of an effect.

All that’s left for Occupy to do, then, is to sit around, waiting for the Next Big Protest–where peaceful protestors will, again, be filmed brutalized by all-too-eager to attack police officers. And then, after that, to hold their nose and vote in November, hoping that after Obama is reelected and, once again, dashes away all of his campaign promises about Hope and Change, people will remember that passively investing their hopes in politicians is a death sentence. Then they’ll take to the streets again, starting the process all over.

In the United States, we tend to view history as something other people (usually white, upper class men) did long ago, not something we all actively participate in on a day to day basis. In school textbooks, we were taught that the American Revolution was the accomplishment of a few incredibly enlightened, well-educated men. We forget that it took hundreds of thousands of people—especially young people, women, and working class men–to support and spread the ideas of democracy throughout the colonies.

The problem with how we view Occupy, then, is very similar. We tend to see Occupy as a spectacle taking place at a distance by people very unlike ourselves. Brutal police officers and their photogenic victims, Occupy-friendly celebrities and artists, black block style anarchists, and our cities’ despotic mayors are the characters in this drama who elaborately battle it out for headlines on the stage of our trash-strewn cities. Like most stories we find captivating as Americans, Occupy has become a newspaper story of violence, celebrity and corruption.

By accepting this view of Occupy, we accept at face value much of what Occupy fought against. This popular narrative of Occupy teaches us that only through violence (whether by smashing a window of a Starbucks or by getting smashed in the face by a cop on a rampage) will we bring attention to our cause—preferably the attention of trend-setting celebrities or some not-entirely-out-of-touch politician.

The true magic of Occupy was that it rejected all of these things. No one had any more power than anyone else at the General Assemblies or in the encampments. At the beginning, nobody in Occupy really cared that we were ignored by the mainstream media. We don’t need a bunch of hacks at Time Magazine to commend us for our ability to protest. The only reason we received such a burst of tepidly-favorable attention from the mainstream media and their star politicians, anyways, was because they sensed a loss of legitimacy if they continued to ignore us. And, besides, the goal was never to get them to take a step back and view what their out-of-touch policies have done to the rest of us in the first place. The parasitic 1% couldn’t care less what happens to the rest of us, so long as we don’t openly revolt.

The goal of Occupy was to get together as a community of equals, to claim a future different than the ones they gave us, and to reignite a tradition of democratic progress that reaches back far into our history. The goals of the slowly evolving Occupy movement were something of an experiment. It was a way of exploring new ways of interacting with others. Of showing each other that we can do very fine without the 1%, thank you very much.

Shrugging off Occupy as a momentary fad or a leftist pipedream is to do a disservice to both Occupy and our collective yearning for a more legitimate community. When Occupy began, there was a feeling in the air that another world was not only possible, but that it was possibly inevitable. Our isolation and alienation no longer seemed like an unbridgeable gap:

“Separations are broken down. Personal problems are transformed into public issues; public issues that seemed distant and abstract become immediate practical matters. The old order is analyzed, criticized, satirized. People learn more about society in a week than in years of academic “social studies” or leftist “consciousness raising.” Long repressed experiences are revived. Everything seems possible — and much more is possible. People can hardly believe what they used to put up with in “the old days.” (Ken Knabb, The Joy of Revolution)

Since those days, over 7,200 Occupy protestors have been arrested in the United States. Many have been beaten and tortured. The media has been strong-armed into not reporting on Occupy except in an unfavorable light, and non-participants (but potential sympathizers) are encouraged to sarcastically roll their eyes at those silly protestors who just don’t seem to get it. In light of all this demoralization, Occupy protestors are left wondering what it was all about, grasping at easy explanations for their continued movement such as “shifting the national dialogue” or hoping that this next week’s protest might suddenly convince the powers that be to change their corrupt ways.

While I’m certainly happy that the “national dialogue” has “shifted” (I no longer feel like a crazy person babbling away about economic injustice) [editor’s note: we support “crazy people” speaking out about economic injustice] celebrating the fact that Obama now has to pretend to give a shit and Romney must now pretend to be human is an incredibly hopeless prospect. This “national dialogue” we speak about is not something that happens when we reach critical mass and the media and the politicians can no longer afford to ignore us. It’s a continued conversation that reverberates among the masses. It’s a process of teaching one another, of questioning the status quo and debating the proper course of action—it’s the sound of agreements and disagreements among individuals who view each other as human beings. It’s the sound of people sharing their visions of a better society and realizing their common goals.

It needs to be remembered that the word “occupy” is a verb. It’s a call to action, not the action itself. The word “occupy” was useful for getting individuals and organizations previously isolated or focused on one-issue grievances out into the streets. Whether the individuals involved wanted to merely overturn Citizens United or overthrow the entire capitalist system itself, Occupy was the first all-encompassing protest movement to occur within many of our lifetimes. Whether or not the word “Occupy” continues to be the word to describe this movement is not important. What is important is that there’s wide community of opposition being formed across many social barriers, and those who hold power are very afraid.

"Humanity needs revolution".

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

June 27, 2012 at 1:40 pm

I just joined Occupy Uganda, online, and I joined Occupy South Africa months ago. Distance is nothing like what it used to be. I talk to people from these movements every week, online or on the phone. And I just sent them my favorite San Francisco Pride photo.

June 14, 2012 at 5:05 am

Stirring words but I’d still lay 2 to 1 odds against Occupy having any future impact.