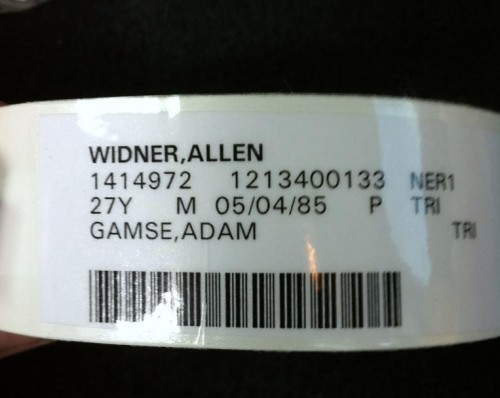

Uninsured healthcare patient Allen Widner, 27, checked into several Alameda County hospitals before receiving the emergency treatment he needed. Photo courtesy Jodi Hernstrom.

By Joe Fitzgerald and Sara Bloomberg

June 29, 2012

Allen Widner began to experience intense stomach pains in early May.

His grandmother called 911 and the 27-year-old was rushed to Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland. He was given Vicodin and discharged — but the pain never stopped.

He returned the next day, was diagnosed with acid reflux and sent home with antacids.

“I felt like I was dying,” Widner said, but the hospital’s staff refused to admit him for the night.

The next day, Widner’s mother drove up from Salinas to visit her son and his partner.

“They didn’t want to tell me because they didn’t want to ruin my Mother’s Day,” said his mother, Jodi Hernstrom.

But she could tell that something was wrong.

Hernstrom drove the family back to Alta Bates’ emergency room for what would be Widner’s third visit for the same abdominal pains.

They waited more than an hour for care as Widner screamed in pain, clutching at his gut.

“I was infuriated. I was so concerned.” Hernstrom said. “Even though he’s 27 he’s still my kid, in pain.”

One of thousands

Widner, of Oakland, now has more than $17,000 in hospital bills. He is one of the nearly 200,000 uninsured residents in Alameda County.

Like many young men, who tend to not seek primary care, he was unaware of his options, including programs like HealthPAC, a program established in 2011 that uses federal funding to provide some 72,000 uninsured residents with health care in the county.

The program is one of many in California that sought to expand health care coverage to the uninsured under a broader blueprint called “Bridge to Reform.”

The program, approved in November 2010, brought $10 million in federal funding to California for expanding health care coverage and transitioning to the stipulations of Obamacare by 2014 – a gamble, since at the time its future was cloudy at best.

Under the newly upheld Affordable Care Act, federal funds wil roll into state coffers nationally by 2013 to pay 100 percent of MediCaid reimbursements – known as MediCal in California – to primary care physicians.

Millions of previously uninsured people across the state have already enrolled in health care through “Bridge to Reform,” including a vulnerable chunk of the population that may be unexpected: the middle class.

Those living above the federal poverty line but who don’t earn enough to afford costly insurance are those most likely to fall through the crachs of health care, said Kathleen Clonan, medical director of Alameda County’s HealthPAC program.

Widner is among them. The Oakland resident was laid off from his video game development job in March. Previously insured through work, Widner was one of those unlucky thousands who had not yet enrolled in a new health plan. And it nearly cost him his life.

Nothing to be done

Widner and his family were told there was nothing that could be done for him at Alta Bates and recommended that he go see a specialist at Oakland’s Highland General Hospital, known nationally as a place so wildly strewn with those in need of emergency care that it’s often compared to practicing medicine in a war-torn country.

Widner’s mother argued with staff at Alta Bates, but said her concerns went unheard. When she wheeled Widner out in a hospital wheelchair, security was called — nurses told the guard that they may be attempting to steal the wheelchair. The family left to try their hand at Highland.

Highland lived up to reputation.

Alta Bates sees about 40,000 emergency room visits every year. Last year, Highland saw more than double that amount, while only having about a third more on-staff nurses, according to the American Hospital Association.

Officials at Highland told Widner he’s had to wait eight hours to see a specialist.

Emergency rooms are overburdened with people without access to primary care, said Sherri Willis, the public information officer for the Alameda County Public Health Department. In some cases, patients may wait up to six weeks to see a specialist.

“[By law] you cannot be turned away for any reason” Willis said, but the level of care provided is not determined by law.

Widner had “unknown abdominal pain,” according to his discharge papers from Alta Bates.

Left improperly treated, the source of that pain almost proved deadly.

The road to better healthcare

While other mothers around California sat down for dinner with their children, Jodi Hernstrom just wanted to see her son live.

Hernstrom fled from Highland with her son and set out for Natividad Medical Center in Salinas — a nearly two-hour drive south — where she was certain her son would get care.

“My ex-husband died two years ago. I’ve had six people die in my family in the past two years. That’s how I knew Natividad would take care of him, from the care they gave Allen’s brother,” Hernstrom said.

Hernstrom could feel her son kicking against the back of her seat, screaming in agony the whole way to Salinas as she slammed her foot against the gas pedal.

While his mother drove, Widner’s partner Becca Hoekstra tried to come to grips with what was happening.

“I kept calculating how much time he had left before he started to die, while trying to rationalize that it could never possibly happen,” Hoekstra said.

“The worst part was that he was barely conscious by this point. He was in so much pain he couldn’t think; could hardly see; could barely talk,” she said. “He would have died without either of us being able to say goodbye. He wouldn’t even know how much I loved him and would miss him.”

It took only two visits to Natividad for Widner to see a specialist. During his first visit, he was given a muscle relaxant to ease the pain. When the pain returned hours later, they ran tests and began treating him for acid reflux — a very common and easily treated condition.

But untreated, the acid had escaped his stomach and tore more than a hundred ulcers up and down his esophagus. The doctors told the frightened family that had he continued “waiting it out,” he may have died.

Specialists in short supply

Programs to help the uninsured are available in Alameda County, including HealthPAC, but access to a specialist is still not guaranteed, Kathleen Clonan said.

“Bridge to Reform” is helping, though.

“Highland hospital is using some of the federal money with health care reform to increase the amount of Gastro-Intestinal specialists” available, she said, but there are still some services that aren’t covered by HealthPAC, such as podiatry, dentistry and optics.

Around three-quarters of Salinas residents who are currently uninsured are expected to become eligible for either Medical or private insurance exchanges under Obamacare, said Harry Weis, Natividad’s chief executive officer.

“It’s a huge positive step forward,” Weis said. “We shouldn’t underestimate that this is the most important legislation since 1965,” when Medicare was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. “Our current model is not sustainable.”

After his experience, Widner isn’t as hopeful about the future of health care.

“Any change is at least a change,” Widner said, but it’s a still tiered system that offers different levels of care for those depending on who can pay for it.

For those like Widner, who have already fallen through the cracks, help from new insurance programs and new specialists may be too little, too late.

“They only seek health care if something is broken or dripping. Young women, in their late teens, come into care around reproductive stuff,” Clonan said. “Young men are the hardest population to reach.”

Outreach and education will remain an important part of improving health care in this country, as millions of previously uninsured people gain increased access to free and reduced-cost health services.

Republican presidential hopeful Mitt Romney has promised to repeal Obamacare if elected in November.

The Hunger Site

The Hunger Site

July 5, 2012 at 9:29 am

This is a violation of patient privacy protection act, and a nice opportunity for identity theft as well.